originally published in The Lawyers Weekly

Can a journalist chronicle a court case 140 characters at a time?

Judge for yourself. Follow trials in Ottawa and London, Ontario where judges in both cases are letting journalists stream events from the courtroom to the Internet via Twitter.

FYI: Twitter is a micro-blogging site where people post short comments – 140 characters or less. (This limit makes knowledge of acronyms like those scattered throughout this article very valuable). It’s free, it’s fast, and fans can follow the streams (accumulations of Twitter posts, or tweets) that interest them.

Throw in numerous tools that let people tweet from smartphones as well as computers and it’s little wonder that Twitter permeates just about every societal niche imaginable.

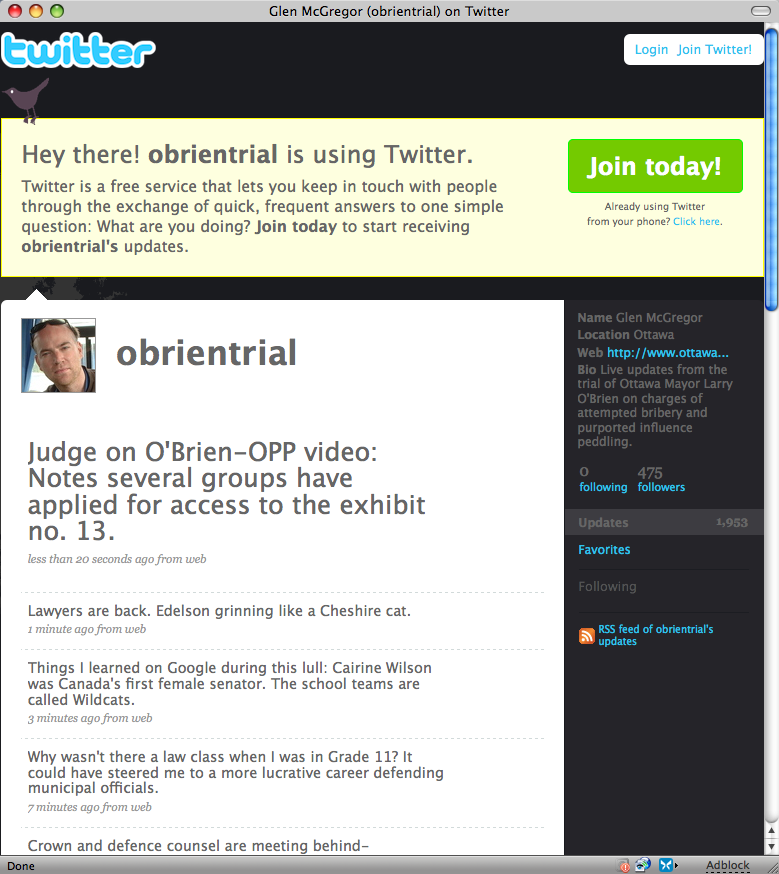

In Ottawa, www.twitter.com/obrientrial (a.k.a. the Ottawa Citizen’s Glen McGregor) is, according to the Citizen, “Twittering up a storm from … the bribery trial of Mayor Larry O’Brien.” FWIW (For what it’s worth), Mr. O’Brien faces criminal charges over allegations of influence peddling.

Meanwhile, you can pick up the latest news on the Bandidos London trial (as well as other information) by visiting Kate Dubinski’s Twitter stream at www.twitter.com/KateAtLFPress.

Many lawyers aren’t yet sure what to think. “This is evolving rapidly,” says Toronto-based Daryl Cruz, Partner and Practice Group Leader, Litigation for McCarthyTétrault LLP. “Six months ago, we probably wouldn’t have had this conversation because it wouldn’t have crossed anybody’s mind.”

Michael Geist thinks this is NBD (no big deal). “Nobody would question the right of the public to attend the trial,” says the Canada Research Chair in Internet and E-commerce Law. “Nobody would question a reporter taking notes at a meeting. Twitter is nothing more than taking notes, with faster dissemination.”

Cruz hasn’t jumped on the bandwagon. “Using new technologies to provide information about a public event can be helpful,” he admits, “but you can’t forget about the countervailing issues.”

One issue is the arguably increased potential for GIGO (garbage in, garbage out). This concern goes beyond a reliance on acronyms run amok (which both reporters have, for the most part, avoided).

Live blogging, even if factually correct, can beget inaccuracies according to Cruz. “Evidence in a courtroom takes time to assume a real shape,” he says. “Real-time sound bites are likely to bear no relation to the sum of the evidence of the witness after a lengthy time on the stand.”

Connie Crosby agrees. “It doesn’t give a lot of room for clarifying context and giving facts,” says the former law librarian and principal of Toronto-based Crosby Group Consulting. She adds that tweets can be taken out of context, as happened when somebody mistakenly attributed an inflammatory tweet about Tamil protesters to Toronto mayor David Miller when, in fact, the comment was merely addressed to Miller.

“Reporters who sit in the courtroom and do not live blog take notes and listen to the whole sequence of events,” Cruz adds. “They get to understand the sum total of the evidence before they prepare reports.”

Geist rebuts the accuracy argument. “If your local newspaper made mistakes every day, it wouldn’t be your local newspaper for long,” he says. “If somebody Twittering a trial regularly makes errors, people simply will not follow that person.”

Crosby claims that trained journalists are less likely to OMIK (open mouth, insert keyboard). “Journalists will often fact-check with lawyers during breaks,” she says, noting that news organizations like The Wall Street Journal are sending their reporters guides that cover Twitter as a medium for reporting.

“I’m pro-citizen journalism, but there’s a lot to be said for the training a journalist has,” Crosby adds.

Do reporters know how to effectively tweet trials? Read the following snippets snatched from the two Twitter streams:

Bandidos trial followers may need to filter Dubinski’s stream to remove non-Bandidos tweets. McGregor, on the other hand, devotes his stream entirely to the O’Brien trial (plus tangentially related thoughts), which suggests a best practice for tweeting court reporters.

There’s a tangential OMG – WTF (oh my god – what the f—) category to consider, when jurors, judges or lawyers prove less-than-judicious trial twitterers (twits?). For instance, an Arkansas firm tried to overturn a $12.6 million judgment by claiming a juror had tweeted about the trial. (In fact, the juror sent comments after the verdict had been delivered, so the judge did not grant a new trial.)

Even after weighing potential pitfalls, Geist is bullish on live blogging. “The premise of court trials, of hearings, is for openness,” he says. “Any steps taken to increase the level of transparency are typically good things.”

“I think we’ll see more Twittering take place in government hearings, events that are nominally open but which few people attend, events that don’t take place behind closed doors but which typically don’t get much attention.”

“Reporters are coming under increased pressure to produce at a faster rate for their readers, almost in real time now,” Crosby notes. “If we want journalists to continue to cover courtroom activities, they must be able to talk about them in real time.”

Whether Twitter has a place in Canadian courtrooms seems a moot point. Reporters may not ask permission to use Twitter in future cases. “It seems like the cat is out of the bag,” Crosby says.

To download a PDF of the article, click CourtTweet.