originally published in Award Magazine

Toronto’s RBC Centre will be the first triple-A office building in Canada to achieve LEED Gold NC status.

“We originally announced the project as silver because we were conservative in calculating the LEED scorecard in terms of what we might be able to achieve,” says Wayne Barwise, senior VP of office development for Cadillac Fairview, which owns the RBC Centre.

“LEED was becoming so important for leasing, for marketing purposes, that the higher the category the better,” adds Stephen Herscovitch, senior associate with B+H Architects. “There wasn’t a huge increase in construction costs to go that one extra step.”

To attain LEED Gold, the Centre boasts “the greatest number of sustainable elements we’ve seen in one place, especially a high-rise,” according to Greg Waugh, senior associate principal and project manager for architectural firm and RBC Centre design architects Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates.

Massive cisterns in the Centre’s basement collect and store rainwater for use in toilets and urinals on the first 300,000 square feet of the building. Meanwhile, Enwave Deep Lake Water Cooling (Lake Ontario water) cools the building, reducing air conditioning costs to a tenth of what they would be using traditional systems.

Also untraditional is the building-wide under-floor air distribution system. “The supply air is delivered through occupant-adjustable flush floor diffusers,” says Dermot Sweeney, principal with Architects, adding “All occupants in the building thereby adjust their own temperature and flow of air.”

Where occupants experience demand-based ventilation, building management will realize increased efficiency, according to Josh Chaiken, senior associate principal and senior designer for Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates. “In a typical system, where the ducts are up above, you heat and cool areas that don’t have to be heated or cooled,” he says.

As well as ductwork, the 18-inch under-floor space also houses cabling for power, data and communications creating a “plug-and-play” environment. “It’s a selling feature when it’s easier to move people around an office,” says Tönu Altosaar, senior partner and managing director, Middle East for B+H Architects.

The underfloor design also eliminates eyesores common to open-concept offices. “You don’t see the PAC poles coming down from the ceiling,” says Herscovitch.

Putting all this equipment under the floors eliminated the need for drop ceilings, and occupants can enjoy exposed concrete eleven feet, three inches above the floor. “The lights shine up onto the light-coloured concrete, which reflects light back to desk level,” says Altosaar.

Creating clean, light-coloured concrete ceilings to maximize light reflection posed a challenge. “Lots of debris gathers on top of slab tables during assembly and the tying of rebar,” says Darius Zaccak, construction manager for PCL Constructors Canada. “We power-washed the plywood to make sure there were no latence left behind from earlier concrete pours.”

To trim energy bills, motion sensors turn off nearby lights if nobody is around. Another system adjusts light levels relative to what the sun provides during the day. “Photo cells on the roof track the sun and help control the automatic window blind system,” says Herscovitch.

“Sunshade louvers on the exterior cut down glare,” Barwise explains. “Also, the interior has retractable light shelves located at the nine-foot level of the curtain wall. They are about two feet wide, and on a dull or grey day, they capture light from the exterior and reflect it further into the building.”

“When light sensors detect a lot of glare, the light shelves automatically fold up into a vertical position, which eliminates two feet of glare coming in the top portion of the floor-to-ceiling windows.”

Should there still be too much glare, the system rolls down blinds behind the light shelves, and lighting inside adjusts as well.

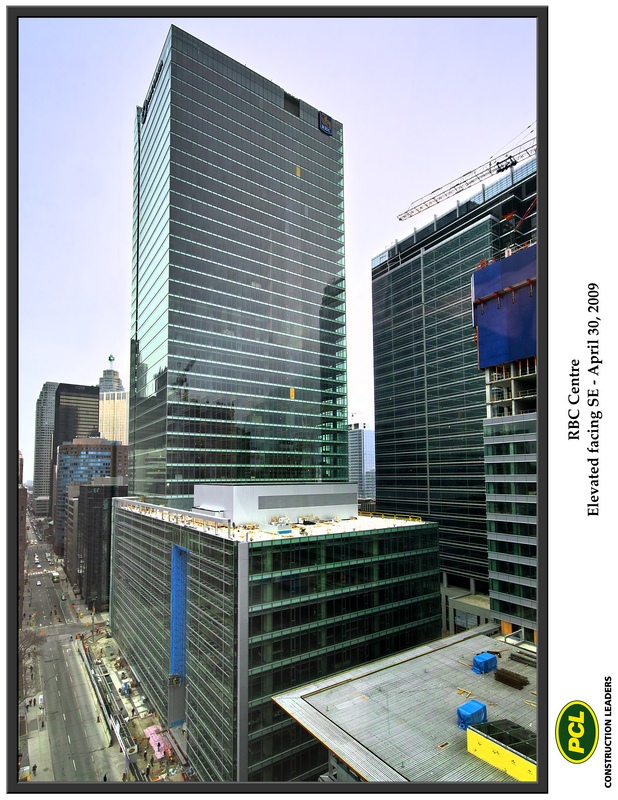

All 41 stories feature a very efficient net to gross, maximizing the amount of leasable area. “On each cantilevered floor slab, columns are 15 feet inboard from the perimeter,” Barwise says. “The glass curtain wall is unobstructed in terms of visibility and utilization at the perimeter.”

Building to LEED specifications involves what Zaccak terms a “parallel process.” He offers sedimentation control as an example. “To maintain strict control of contaminants during construction,” he says, “we had to understand what they were, put methods in place for controlling them, document these methods, share them with our consultants, have them reviewed and accepted and then document their implementation throughout the construction process.”

Given its size and location at a bustling downtown Toronto intersection, the Centre’s builders took time while planning the project to collaborate with its future neighbours and the city. To accommodate heavy inflows and outflows of materials, “we had to create a traffic flow plan that works for everybody,” Zaccak says.

The Centre shares a loading dock with Simcoe Place, a current neighbour, and the soon-to-be-built 53-story Ritz-Carlton Hotel and private residences (which Cadillac Fairview is also developing). Loading facilities had to be initially enlarged, then moved at different phases of construction. “Even though it was a construction site, we had to ensure it would continue to operate for the existing building,” says Barwise.

Meanwhile, labour and carpenter strikes in 2007 plus adverse weather during the winter of 2007-2008 caused scheduling concerns. “Overall, we lost close to two months,” Zaccak recalls. “We still met the original deadline under which the deal was made, to the day. Our first tenants moved in on the first of June, 2009.”

Chaiken expected another challenge: “when owners sharpen pencils for value engineering, looking for places to save money on the building,” he recalls.

“PCL did a great job of estimating costs and keeping them under control,” he adds. “After the value engineering phase, much of what was important to the building was left intact. Cadillac Fairview did not want to diminish the quality of the design.”

Sweeney sees LEED as suffering from “underlying incorrect assumptions in the industry: green buildings cost more; change costs more; new ideas cost more.”

“Typically, for every dollar you spend on increased capital, you add 10 cents per square foot in rent,” he explains. “But here, the capital costs are competitive and the Centre boasts dramatically lower operating costs.”

“There are some challenges in the marketplace right now,” Barwise admits, noting that 75 percent of the building has been leased. “The top of the building, the best space available, is still available to lease, so we’re confident that the remaining 25 percent will be leased, but we anticipate that it will take a little longer than originally planned.”

But Barwise remains bullish. “The building will achieve energy savings of 40 to 50 percent, so when economic times are tough, companies will cut back on costs to save money, and one way to do so is to move into a building with reduced operating costs.”

For a PDF of this article, click RBC_Centre_LEED_Gold.

For building specifications, click RBC_Centre_building_specs